WEEK 7: Models of domesticity through history

by isabellazulli

The 17th Century DUTCH INTERIOR

The mid seventeenth century saw the subdivision of the Dutch home into day and night uses, and into formal and informal areas. The upper floors of the house began to be treated as formal rooms, only used for special occasions. Other rooms in the house were reserved for sleeping and were for private use only.

The 17th century Dutch home was not necessarily innovative however, as it still retained many medieval features. It was the blending of the old and new that gave the Dutch home its unique characteristic features. The Dutch prized three things above all else, firstly their children, secondly their homes and thirdly their gardens. The growing importance of family in Dutch society influenced the new design of the family home.

17th Century Dutch Interior, Vermeer, ‘Carrer de Delft’, 1657-1658, Amsterdam, Rijkmuseum

“Home brought together the meanings of house and household, of dwelling and of refuge, of ownership and of affection.” John Lukas, The Bourgeois Interior

The furniture and decoration of a 17th century Dutch home were used to convey the wealth of its owner. Benches and stools were still present in less prosperous homes, however as in England and France, the chair had become the most common sitting device (the chair was only found in royal homes previous to this period). In comparison to the French Bourgeois that was crowded and chaotic, the Dutch interior was simple and sparse. The Dutch didn’t want the interior to be crowded as they wanted to feel a sense of space that the room and the light produced. They created spaces that were uniquely intimate and private.

‘The Fat Kitchen’, Jan Steen, 1650

The feminisation of the Dutch home in the 17th century was one of the most important events in the evolution of the domestic interior. The main cause of this was the changed limited use of servants. Dutch married women had “the whole care and absolute management of all their Domestique”, which included taking care of the cooking. This saw the increasing importance of the kitchen room in the home. The woman became master of the house.

“Domesticity, privacy, comfort, the concept of the home and of the family: these are, literally, principal achievements of the Bourgeois Age.” – John Lukas, The Bourgeois Interior

17th Century Dutch Interior (Vermeer)

Pieter de Hooch

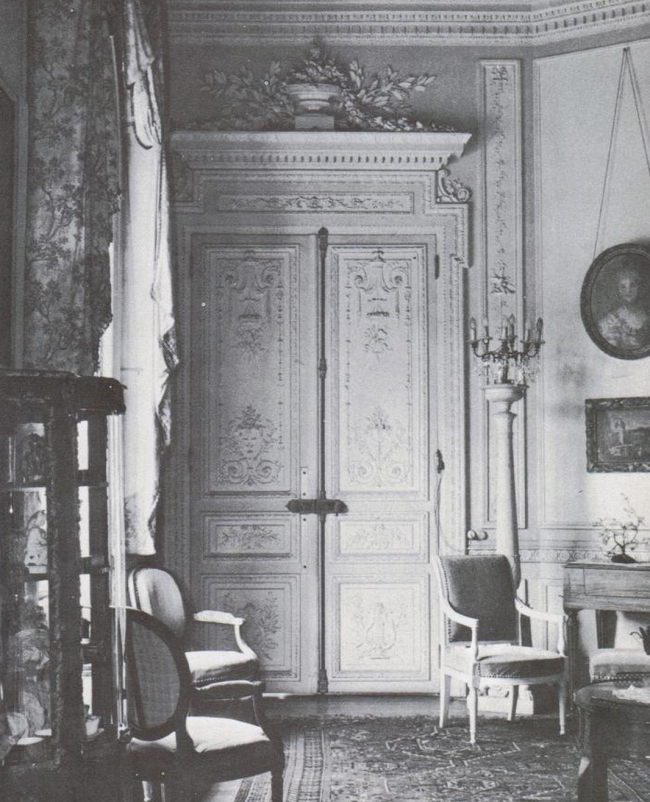

The 18th Century FRENCH DOMESTIC INTERIOR

The eighteenth century saw the rise of a number of highly influential interior designers and architects such as James ‘Athenian’ Stuart, Robert Adam and Horace Walpole. Similarly to the the seventeenth century Dutch home, the eighteenth century parisian interior floor plan was still very much separated between public and private spaces. However, unlike the dutch home, the French architects and designers were very fond of extravagant detailing and colour.

French Pavilions of the Eighteenth Century, Jerome Zerbe & Cyril Connolly

An 18th century upper class bedroom, Paul Lacroix

An example of an extravagantly designed french interior from the eighteenth century is Horace Walpole’s ‘Strawberry Hill’. The house was built in stages from the late 1740s to the 1790s and used by Walpole for both entertaining and as a private retreat. Walpole was an influential historian, collector and social commentator, which heavily influenced the style of his architecture. The eighteenth century saw a revival of Gothic style in french interiors. Walpole’s fascination with history and art led him to design and build Strawberry Hill through a Gothic lens.

Strawberry Hill, Horace Walpole

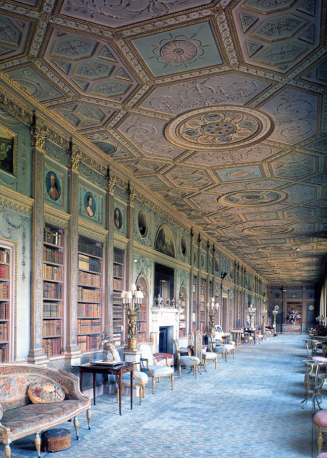

Robert Adam was one of the most celebrated architects of his day. Adam was famous for his neo-classical architectural style. His main achievement was the development of a unified style that extended beyond architecture and interiors to include both the fixed and moveable objects in a room. Similar to Walpole, Adam incorporated design ideas from historical periods, such as ancient Greece and Rome into the form and decoration of a space.

Detail from a ceiling design for 5 Adelphi Terrace, by Robert Adam, England, 1771

Syon House, Robert Adam, West London, 1760

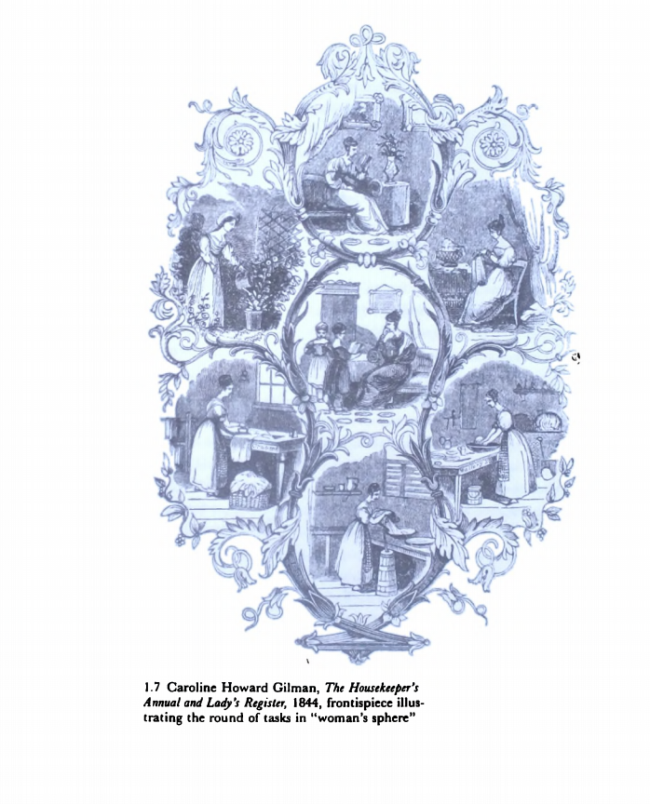

Delores Hayden’s ‘Grand Domestic Revolution’

“Women’s work” comprised of activities such as cooking food, caring for children and cleaning the house. These activities were a women’s job, however were to be performed without pay in domestic environments. This generated a huge division between men and women. The of the first feminist groups in the United States of America were known as ‘Material Feminists’ as they dared to define a “grand domestic revolution” in women’s material conditions.

Delores Hayden ‘Grand Domestic Revolution’

Their main goal was to demand economic remuneration for women’s unpaid household labour. They proposed ‘a complete transformation of the spatial design and material culture of American homes, neighbourhoods and cities’. In order to overcome patterns of urban space and domestic space that isolated women and made their domestic work invisible, they developed new forms of neighbourhood organisations such as the day care centre, the public kitchen and the community dining club. By redefining housework and the housing needs of women and their families, they pushed architects and urban planners to reconsider the effects of design on family life.

Delores Hayden, ‘Grand Domestic Revolution’

1960s UTOPIAN MOVEMENT

The 50s and 60s saw an immense shift in domestic labour. Women were less required to do all the domestic labour within the home as it became more of a family responsibility to work together to get all the chores done. This period gave women the freedom to leave the home and explore leisure activities. This freedom was mimicked in the house plan, as open plan living saw a breakdown of boundaries between public and private rooms of the home.

The confident 1960s women.

The first example of how the space of the kitchen shifted from a small, closed in space to an open plan space was the Frigidaire Kitchen, which was designed in 1957. This kitchen was designed to give women more freedom from domestic activities as it allowed them to balance both domestic life with leisure activities. The design of the kitchen was quite striking in its theatrical ability. The individual pieces of the kitchen were temporary, meaning it could be altered and moved to suit the needs of the user. The temporality and freedom of the kitchen allowed for completed efficiency, a concept that was prominent in society after the second world war. This kitchen gave women confidence to be independent in how they ran their homes and their lives as it gave them more control.

The Frigidaire Kitchen, 1957

Another suitable example of the modern day kitchen was Fred Antelline’s 1961 Kitchen, which was built in a home in Rancho Santa Fe. It is popularly known as the “pleasure island” kitchen. The design of this kitchen created a whole new interaction and system to kitchen activity. Instead of the kitchen being being placed in a space purely for women to cook in, shut off from the rest of the home, Antelline designed it so that the entire family and occasionally visiting guests could be a part of the cooking process. The breakfast bar/island bench created a space for face-to-face preparation that made it “easy on the wife”. Everyone became part of the process and cooking became a form of entertainment and fun.

Fred Antelline’s 1961 Kitchen

Relation to Semester 1

The 17th Century Dutch home required a separation of formal and informal space. Similarly in projects 2 and 3, in redesigning the space of the NSW Institute of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, it was crucial to create a division in the space. The NSWIPP did not require a division between the formal and informal, but rather a division between the public and private spaces of the building. The division of public and private space was crucial in being able to provide a comfortable space for three different users. The building provided public space through the cafe intruder as well as the exterior garden space that could be used for dadirri and other purposes by the local community. The public space of the building was also designed for institute members by providing them with an open plan living, dining and entertainment area on the ground floor of the building. The private space of the building provided institute members and invited guests with training and presentation facilities. It then also generated a very private space for a possible patient to be provided with therapy services within the building. Without the division of public and private space, the building would not be able to provide facilities and services to all three users of the institute.

References:

1.Rybczynski, Witold, ‘Domesticity’ , in Toward a New Interior; An Anthology of Interior Design Theory,Princeton Architectural Press. Ed Lois Weinthal 2011.

2. Hayden, Delores. ‘The Grand Domestic Revolution: A history of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighbourhoods and Cities’ Cambridge: MIT Press, 1981 pp. 1-30 Introduction.

3. Pohl, Ethel Baraona & Puigjaner, Anna & Najera Cesar Reyes, Blurring the Kitchen Work Triangle in Archis Magazine, Volume 33 Interiors. ed. Oosterman Arjen ( Netherlands: Stichting Archis, 2013) pp.118-122

4. ’18th Century Interior Design’, Victoria and Albert Museum,accessed 25th April 2014, <http://www.vam.ac.uk/page/0-9/18th-century-interior-design/>