WEEK 4: How did the envelop of the interior develop historically?

by isabellazulli

How did the ‘envelope’ of the interior develop historically? How does it relate to the rise of companionate marriage, the nuclear family and what comes to be known as the ‘bourgeois’?

The word ‘interior’ has changed in meaning throughout history. The first English meaning of interior in the late fifteenth century was ‘the basic divisions between inside and outside, and to describe the spiritual and inner nature of the soul’. From the early eighteenth century, interiority was used to ‘designate inner character and a sense of individual subjectivity’. At the end of the eighteenth century, the interior came to ‘designate the domestic affairs of a state, as well as the interior sense of territory that belongs to a country or region’. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that the word ‘interior’ became to mean ‘the inside of a building or room, esp. in reference to the artistic effect; also, a picture or representation of the inside of a building or room’.

The first use of ‘interior’ in the domestic sense is dated 1829. This is when the interior emerged as the ‘Bourgeois Domesticity’ in the nineteenth century. The bourgeois emerged as a space separated from sites of work and productive labour, to become ‘a place of refuge from the city and its new, alienating forms of experience’.

Marriages in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were typically arranged by a father and a man willing to marry his daughter. The daughter was treated like property and was traded or sold to a man, usually a lot older than her. By the mid-18th century, companionate marriages became more common, mainly in the upper and lowest classes. Companionate marriage is a marriage in which the partners agree not to have children and may divorce by mutual consent, with neither partner responsible for the financial welfare of the other. Companionate couples were affectionate and chose to spend much time together because they married for love and friendship. The companionate marriage depended on equality and sharing between man and wife. Industrialisation and capitalism saw and increase in the nuclear family (term used to define a family group consisting of a pair of adults and their children) as it became a financially viable social unit due to the influences by church and theocratic governments. The growth of nuclear family influenced the design of interiors.

A seventeenth century dutch interior, nuclear family (Pieter de Hooch, 1665).

Discuss the domestic interior’s evolving relationship to the public sphere.

Two versions of the modern interior emerged in the middle years of the nineteenth century. One was linked with the idea of the ‘home’ and the other was associated with the worlds of work and commerce. Similarly to its middle-class female occupants, the domestic interior refused to be confined to the home. This is where we began to see a blurring between the two spheres of public and private space.

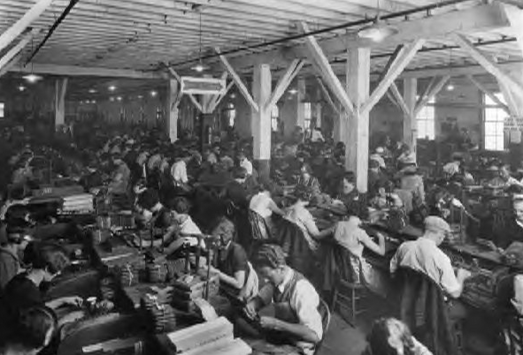

The domestic interior shifted into the public sphere in the same way that domestic manufacturing was shifted into factory manufacturing. The advent of factories had put an end to domestic manufacturing, some examples being clothes making and fruit bottling. Although these goods remained domestic necessities, women were forced to buy them outside the home. This shift to mass production through industrialisation also took the domestic interior into the public sphere.

The domestic chores, such as making clothes, were now being mimicked in factories. This was the beginning of the shift of the private to the public.

Industrialisation is the process of social and economic change that transformed the way people and the community lived.The domestic interior exposed itself to the public sphere through its developing relationship with the growing mass media of the time. The growth of mass media was a key feature of industrial modernity, through mass production and mass consumption. An association was formed between the media and the domestic sphere, which facilitated an enhancement in consumption of goods for the home. Magazine images, trade catalogues and other printed material idealised the domestic space, which then stimulated desire and encouraged consumers to construct their own current domestic interiors through the purchase of new interior products.

Charlie Chaplin staring in the 1936 film ‘Modern Times’ which he wrote and directed. His character struggles to survive in the modern, industrialised world.

Industrialisation and the growth of factories saw an increase in the number of people moving from the countryside into townships as people were looking for better-paid work. Towns were continuously developing and growing as industrialisation took over. The growth of these towns saw the introduction of community services and public spaces. An example of the developing relationship between private interiors within the spaces of public interiors is the shopping mall. With the rise of industrialisation and growing mass production and consumption, there was a rise in the development of public shopping malls. Within this hustle and bustle of mass shopping would be what people knew as a private lounge interior. This showed a clear shift of the domestic interior into the space of a public sphere. The lounge area in this public space would contain comfortable armchairs, a large carpet and potted plants – a scene that had been removed from its more familiar private environment and repositioned in a public space. This space that was known to people as a private interior space, offered comfort and refuge from the growing world of work and commerce.

A modern shopping mall interior (Sparke,P. 2008)

References:

1. Rice Charles, Rethinking Histories of the Interior’ in Intimus; Interior Design Theory Reader, Great Britain: Wiley-Academy 2006 pp. 284-291

2. Sparke, Penny. ‘Introduction, The Modern Interior, London : Reaktion Books, 2008 pp. 7-18

3. Pile John, ‘A History of Interior Design’, London: Laurence King Publishing, 2000. pp. 8-9