WEEK 8: Encounters

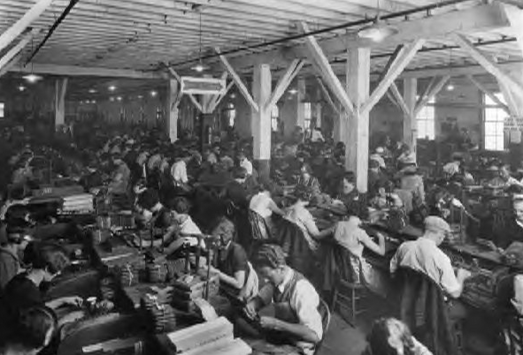

Inhabited spaces demand to be understood less as a collection of objects and more as a collection and articulation of human relations – as the traces of the relationships people make with one another.

Discuss via text and analysis diagrams how we can read the various plans discussed in the text as an articulation of the relationships between inhabitants and an articulation of their behaviours.

Although interior spatial designers may not like to admit it, the interior design of a building will always come after the architecture of the building. The architectural structure of a building must be designed, generated and built before an interior designer can create spatial experiences within the interior of the structure. Interior space is intricate and complex and includes an eco-system of relationships. An interior has the ability to augment encounters between individuals who inhabit and occupy the space. However, the interior also has the ability to hinder such encounters through the design of its circulation.

Robert Evans – Figures, Doors and Passages

“The struggle to find a home and the desire for the shelter, privacy, comfort and independence that a house can provide are familiar the world over.”

The exploration for privacy, comfort and independence through the intervention of architecture is quite a recent idea. When these words were first used in relation to household affairs, their meanings were quite difference from those we now comprehend.

The architectural plan has the ability to describe the nature of human relationships as humans inhabit these spaces and leave traces and records behind. Showing how a space is occupied through diagraming or simple human figures is crucial to understand and gain a sense of how the space is actually used. Without this documentation we cannot understand how the space differs from any other space. The way in which humans inhabit and occupy a space is generally absent in even the most extravagantly illustrated buildings. This is where we begin to see the importance of interior-spatial designers, as they are able to create interior experiences within the structure that an architect has designed and built.

The Madonna in a Room

Raphael was an influential painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its ‘clarity of form and ease of composition and for its visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur’. During the Italian High Renaissance period, the interplay of figures in space begun to dominate painting. In periods previous to this, the representation of the body focused on physiological detail: the articulation of limbs, the modeling of sinew, flesh and muscle, and the rendering of individual beauty. It wasn’t until the sixteenth century that bodies were reduced into the graceful and sublime. The sixteenth century saw a decent from their pedestal to become engulfed by animated groups of familiar figures sharing their company as in Raphael’s Madonna dell’ Impannata (1514), typical of so many ‘holy family’ portraits.

Raphael’s Madonna dell’ Impannata (1514)

The Door

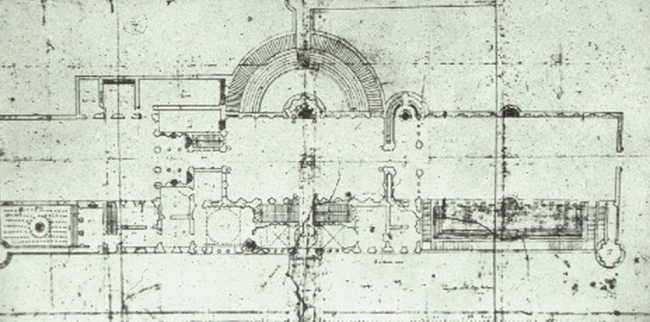

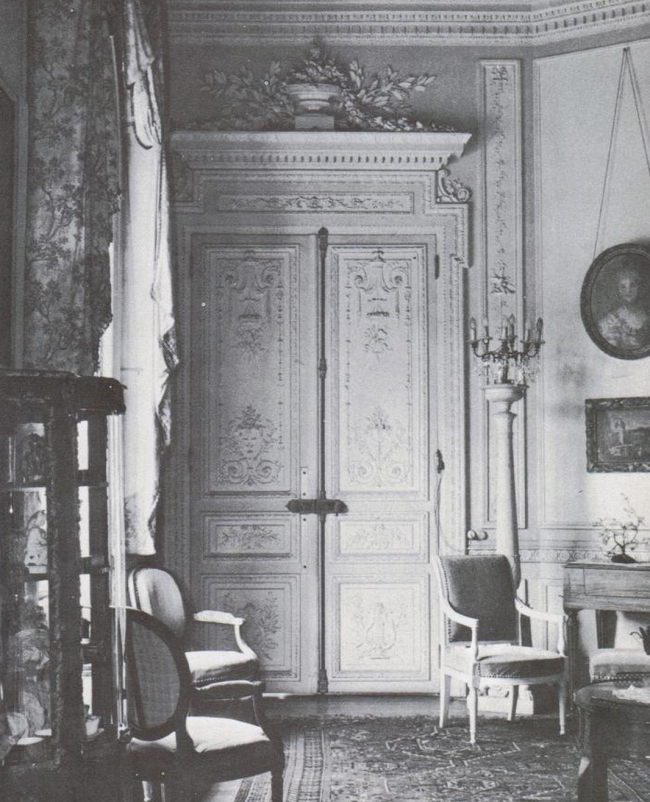

The Villa Madama, located just outside Rome, was designed by Raphael around 1518. The Villa Madama was where we began to see thought going into how the space was to be inhabited by humans. The plan of the Villa Madama was designed to study social relationships through two organisational characteristics. These characteristics are crucially important evidence of the social milieu it was meant to support. Firstly, rooms have more than one door, some have two doors and some have three or four. Although this design concept is thought of as a fault in domestic buildings today, it was preferable in the time of Italian High Renaissance as it meant that there was a door wherever there was an adjoining room, making the house a matrix of discrete but thoroughly interconnected chambers.

Villa Madama Interior

“It is also convenient to place the doors in such a Manner that they may lead to as many Parts of the edifice as possible.” – Alberti

Similarly to all domestic architecture prior to 1650, the Villa Madama had no qualitative distinction between the way through the house and the inhabited spaces within it. Everything we create uses the past to the design the new. In Raphael’s case he used the knowledge and theory of the Ancient Greeks to design the Villa. The main entrance was situated at the southern side of the building. Raphael used pathways, staircases and doorways to create a framing mechanism for human intercourse. It was inevitable that during the course of a day paths would intersect, and that every activity was likely to cause intercession unless very definite routes were taken to avoid it.

The Villa Madama Floor Plan

Passages

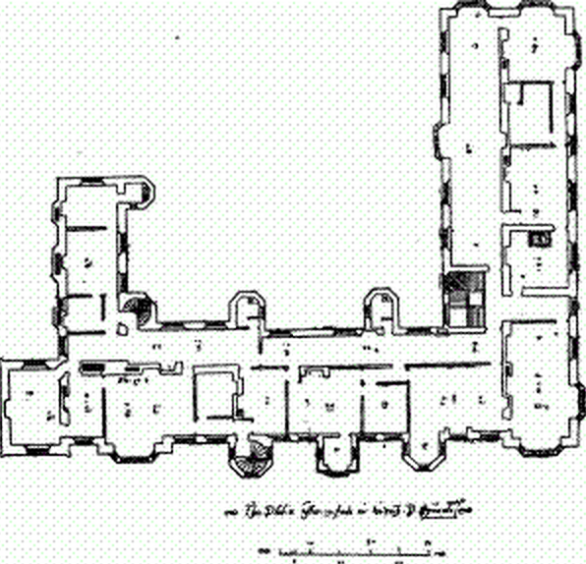

The first recorded appearance of the corridor was in England at the Beaufort House in Chelsea, which was designed by John Thorpe in 1597. “A long entry through all” was written on the house plans, which proved the power of the idea that was beginning to be recognised. To Thorpe, the concept of the corridor was something of a curiosity as he continued to experiment with the idea.

Beaufort House floor plan shows a clear idea of the corridor connecting all rooms of the house.

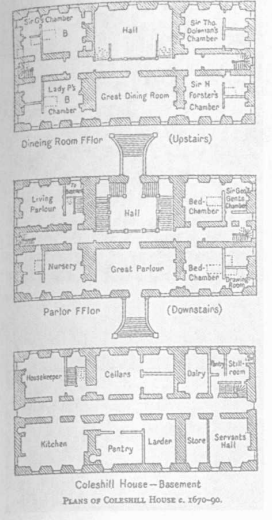

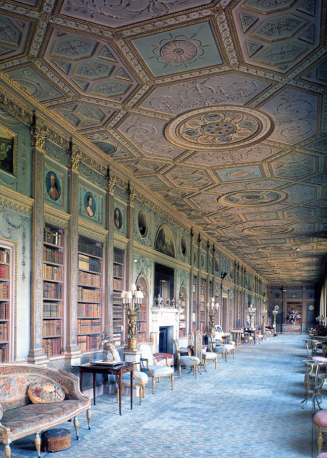

Following 1630, these changes of internal arrangement of the home became very evident in houses built for the upper classes. Houses would contain an entrance hall, grand open stair, passages and backstairs merged to form a network of circulation space, which would reach every major room in the house. Another great application of the corridor is the arrangement of the Coleshill house in Berkshire which was built by Sir Roger Pratt between 1650 and 1667. Every floor in the home comprises a passage that tunnels through the entire length of the building.

Coleshill House Floor Plan showing the central corridor leading to the many rooms of the house.

The Body in Space

The social aspect of architecture, which surfaced for the first time as an integral feature of theory and criticism, had more to do with the fabrication of buildings than the occupation of buildings. However, the social aspect as shifted in emphasis to place more importance on the procedures of its assembly and how bodies occupy and use the space.

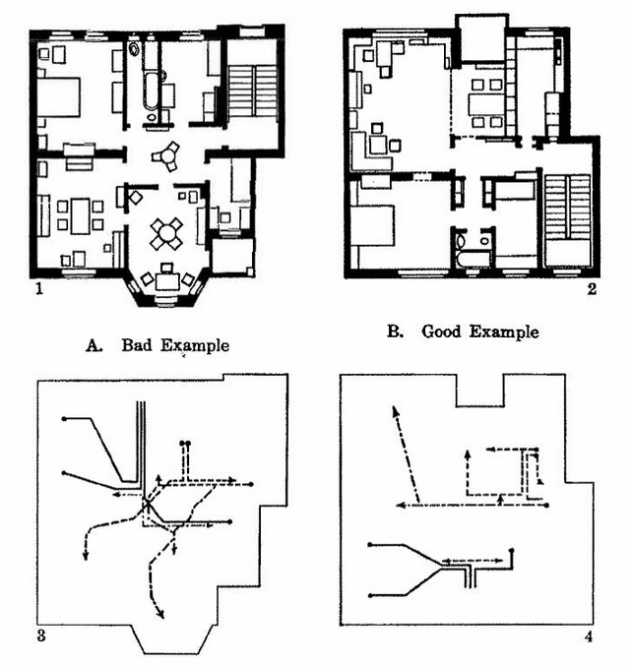

‘The Functional House for Frictionless Living’ designed by Alexander Klein in 1928 was an unusual project that had to consider how to design a home that would fit multiple families comfortably and without conflict. The project started with research carried out by Klein for a German housing agency. Klein used line diagrams to reveal the superiority of his improved house plan. Pathways remain entirely distinct and do not touch at all initiating complete frictionless living. The justification for Klein’s plan was ‘the metaphor hidden in its title implying that all accidental encounters caused friction and therefore threatened the smooth running of the domestic machine: a delicately balanced and sensitive device it was too, always on the edge of malfunction’. Klein’s clever design meant that one could move through the space without encountering one another.

Klein’s Line Diagrams showing frictionless living through improvement to circulation.

The Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa inherited the renaissance style to reinterpret the past. Scarpa would use medieval sculptures throughout his interiors to show relations within a space. In 1953, Scarpa was commissioned to renovate Palazzo Abatellis in Sicily, which was a prestigious building from the last decade in the 1400s. He was able to make the resulting Galleria Nazionale di Sicilia into one of the most impressive museums in Italy.

Carlo Scarpa’s Staircase – so perfectly designed for the body that it does not require a handrail.

Scarpa used the plans to create relationships between the art and the architecture through gaze. He used the architecture of the building as a performance for how we inhabit it and thought of the figures and sculptures being able to move. Scarpa carefully constructed views within the space. The sculpture of Eleanor of Arogon is placed at the end of a corridor. An individual approaches her through a sequence of corridors and arches, which creates a frame for the sculpture. This is an example of how Scarpa understood bodies in space.

‘Elanor of Arogon’ through the frame of the room.

Relation to Semester 1

In redesigning the space of the NSW Institute of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy in Projects 2 and 3, it was crucial to think about how the spaces would be inhabited by humans. The project went beyond thinking about the functions that the institute required, to think instead about how these functions would cooperate together and how the multitude of users would use these separate functions. Improving circulation was a major theme in redesigning the spaces. Three circulation patterns had to be designed in a way that they would comfortably work together to make the building as a whole work for three different users – the institute members, the public and the patient.

References:

1. Evans, Robin. ‘Figures Doors and Passageways’ in Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays, Architecture Association, UK 1997, pp. 42-57

2. Evans, Robin. ‘Rookies and Model Dwellings, English Housing Reform and the Moralities of Private Space’ in Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays, Architecture Association, UK 1997, pp. 93-117